We can all agree that shoulder pain is frustrating. Shoulder function is something people rely on constantly. Getting dressed, showering, feeding oneself, driving, lifting weights, doing pushups, writing, and many other daily activities all depend on healthy shoulder function. Most people rely on their shoulders every day.

There are many possible causes of shoulder pain, but if you have been told you have scapular dyskinesis, scapular instability, or scapular dysfunction, which are essentially different labels for the same idea, there is something important to understand. It may be an uncomfortable truth at first.

Are you sure? Really sure? Alright.

There is no such thing as a dysfunctional scapula.

That may come as a surprise, but it is important to take a closer look at the language we use. The word dysfunctional has no place in conversations about how bodies move. It reinforces the idea that our bodies are fragile or broken, which can lead to hesitation, fear avoidance, and an increased risk of recurring injuries.

How does that happen? Our good friend Dumbledore summed it up well:

“Words are, in my not-so-humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic. Capable of both inflicting injury, and remedying it”

(his beard is filled with wisdom)

Calling a scapula dysfunctional implies that there is a single correct or normal way for a shoulder to move. Anyone labeled as dysfunctional is then seen as abnormal, incorrect, or at risk of hurting themselves. Terms like dyskinesia, abnormal mechanics, and instability create similar problems. They are binary. You are either normal or abnormal, with no room in between.

This kind of mental framing often leads to self-limiting beliefs. People given these diagnoses frequently avoid activity out of fear of making things worse, which ironically tends to make things worse over time. Just because a shoulder is not working the way someone wants does not mean something is wrong with it. It simply means there are a few things that need to be addressed.

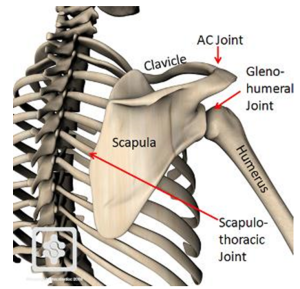

To understand this better, it helps to look at the anatomy of the shoulder. There are three main structures involved: the ribcage, the scapula, and the humerus. The scapulothoracic joint exists between the ribcage and the scapula, while the glenohumeral joint connects the scapula and the humerus.

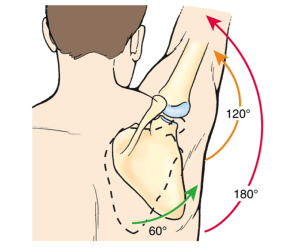

The scapula contributes roughly 30 percent of total shoulder motion and functions as a floating joint with no direct bone-to-bone attachment to the rest of the body. The upper arm bone, or humerus, sits in a socket on the outer edge of the scapula. As the scapula moves, the socket moves with it, allowing the shoulder to orient itself in many different positions. This is what allows the hand to be placed in such a wide variety of positions.

The shoulder has more range of motion than any other joint in the body. With greater available motion comes greater complexity and a higher demand for control. This is where the discussion of stability usually enters the picture.

For this discussion, stability means the ability to resist unwanted motion or return to a desired position after being moved. This definition explains why common treatments for an “unstable” shoulder often include exercises like BOSU planks, reactive drills where a therapist applies unpredictable forces, or lifting weights attached to bands. The intent behind these exercises is good, but the application is often flawed. These drills are complex and involve many variables. For someone already dealing with shoulder issues, that level of complexity can be overwhelming and lead to inconsistent results.

A more effective approach is to start by developing passive motion so the shoulder has access to the positions it needs. The next step is active motion within that newly available range. From there, the focus should shift to producing force in those positions and building strength and consistency in the desired movement patterns.

Only if the issue persists after these steps should more advanced and variable exercises be introduced. For example, a client should not perform any type of unstable surface pushup until they can clearly demonstrate twenty clean and consistent strict pushups first.

Highly variable and dynamic exercises may look impressive, but they belong at the top of the pyramid, not the bottom. The foundation has to be built properly before progressing upward.

If you have been struggling to get your shoulders back to where you want them to be and feel like you have tried everything, returning to the basics and mastering them using this progression can make a significant difference. If this cannot be sorted out independently, working with a skilled professional who understands this process can be extremely valuable. There is nothing wrong with the shoulder. It is simply having difficulty managing complexity right now.