(The #1 Most Overlooked Aspect Of Hip Mobility)

“My hip flexors are always so tight.”

“I always stretch but my hips just feel stiff again later.”

“My foam roller is my best friend, why aren’t my hips more flexible?”

Stiffness or feelings of tightness around the hips are some of the most common complaints we hear from friends, family, and patients. Stretching is also the most common solution people believe they need more of.

At first glance, this makes sense. Something feels tight, stretching gives temporary relief, so doing more stretching should fix it.

But what if that view is incomplete.

All of these statements have something in common. The strategies being used are not addressing what is actually driving the issue.

To understand what more effective strategies look like, we need to first understand how muscles actually work.

Kinesiology 101: What Is the Job of Our Muscles?

Muscles attach to tendons, and tendons attach to bones. Muscles are simple. When they contract, they shorten, flatten, and compress to create movement.

When they are not contracted, they exist in a more lengthened and expanded state.

Notice what term is missing here. Tightness.

Muscles themselves are not tight. They exist on a spectrum from relatively compressed to relatively expanded. Their behavior is largely dictated by the position of the bones they attach to.

Muscles of the Hip Complex

Let’s use a specific example to make this clearer.

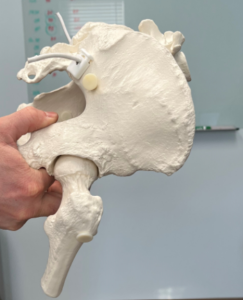

One of the most important muscles in hip mobility is the psoas major. This is your primary hip flexor and it is considered a biarticular muscle because it crosses multiple joints. It runs from the lumbar spine, across the pelvis, and attaches to the femur.

Because of this, the behavior of the psoas is influenced by the position of the spine, pelvis, and hip.

If we are trying to change how this muscle behaves, we must consider all three of those regions.

How Position Drives Hip Flexor “Tightness”

Now let’s look at a position that would cause the psoas to be more shortened or compressed.

When the lower back and pelvis are oriented forward into an anterior position, the attachments of the psoas are brought closer together. This places the muscle in a position where it is already shortened and primed to contract.

This is one of the most common postures seen in people who complain of tight hip flexors.

Now consider one of the most common hip flexor stretches people perform. The individual lunges forward and arches through the lower back while trying to stretch the front of the hip.

While a stretch sensation is often felt, the position of the pelvis and spine has not changed in a way that would allow the hip flexors to truly lengthen. In fact, this position often reinforces the same forward orientation of the pelvis and spine that created the issue in the first place.

What is frequently happening is not a stretch of the hip flexors, but increased pressure at the front of the hip joint and capsule.

The muscle behavior has not changed. Only the sensation has.

A More Effective Approach to Hip Mobility

Rather than forcing static stretches, a more effective strategy is to first address joint position.

An exercise like the hooklying two arm reach is often far more effective. This position places the spine into relative flexion, brings the pelvis into a more posterior orientation, and allows the hip to extend. All of the regions that influence the psoas are addressed at the same time.

This creates a genuine opportunity for the hip flexors to move into a more lengthened and expanded state.

The same principles can be applied in movements like a half kneeling cable press. This positions the pelvis and hip to encourage length through the hip flexors of the down leg, while the pressing action reinforces a spine position that influences the upper portion of the psoas.

An added benefit is that these movements improve mobility while also building strength and coordination, instead of requiring separate time dedicated solely to stretching.

The Takeaway

Muscles do not get tight. Tightness is a sensation.

Muscle behavior exists on a spectrum from relatively compressed to relatively expanded, based on the position of the bones they attach to.

If stretching has not improved your hip mobility, it is likely because position has not been addressed. When you start respecting joint position first, changes in muscle behavior follow, and results tend to come much faster and last much longer.